Code Breaking and Wireless Intercepts

From the earliest days of Marconi's work with wireless it became evident that for military use wireless did have one serious flaw. The transmitted signals are impossible to hide, are open to all, and the source is easy to locate. Unless it was used with complex codes and ciphers and the operators always acted within the rules anyone could listen in. In Russian-Japanese war of 1902, both sides were intercepting each other's wireless communications. It was termed 'wireless reconnaissance'.

During World War One wireless intercepts were used as early as August 1914 when German intelligence was able to listen into wireless messages being transmitted from the Russian Army HQ in Poland. The Russian Army used wireless to coordinate its campaigns but it took no precautions against interception and did not encode its traffic. Amazingly all messages were transmitted 'in clear', no attempt having been made to encrypt them (the Russian author Solzhenitsyn has said that the Russian Imperial high command somewhat naively relied on transmitting late at when it was assumed that the Germans would have gone to bed and would not be listening).

One Russian General officer termed the Russians use of plain text and failure to take precautions 'unpardonable negligence'. The Austrians had integrated their intercept service into their Chancellery cryptographic section at the beginning of the war and they regularly intercepted and decrypted Russian traffic all throughout the war.

The intelligence gathered directly contributed to the German victory at Tannenberg blunting the Russian advance west. The Germans had all of the Russian traffic in hand and readable, overheard by the German radio station at Thorn and in Koenigsberg in East Prussia. While the Germans may not have made as much use of this traffic as its importance would dictate, Generals Paul von Hindenberg and Erich Ludendorff could and likely did know as much about what the Russians would do as they did themselves. Tannenberg showed how important intercepts could be, and the Germans set up wireless intercept stations on all fronts.

As WW1 dawned it was clear that the intelligence services needed both professional and well organised wireless reconnaissance and wireless direction finder services. The very risk of transmission interception and location meant that ships frequently used to communicate by reception only, often until they made contact with the enemy.

On the first day of the war, a British ship dragged up Germany's transatlantic telegraph cables and cut them. From that time on, the Germans had to use radio links or telegrams sent through neutral nations, and both methods left them open to interception. As the Germans had advanced into Belgian and French territory where telegraph lines had been cut, it also forced them to rely on wireless. The French and British, in contrast, only absolutely needed to use wireless to communicate with ships at sea.

At the outbreak of the war, Britain really had no formal code breaking operation. But as the British Admiralty's intelligence service began to intercept German wireless messages it was quickly recognised that a formal cryptanalysis organisation was needed. Volunteer code breakers were found in the country's naval colleges and universities.

At the very start of the War, Marconi engineer Maurice Wright took the first batch of received German messages to the Marconi New Street Works Manager, Andrew Gray, who was a personal friend of Captain Reggie Hall, the head of the Naval Intelligence Department. Captain Hall was the dominant figure in British Intelligence during World War I and was responsible for cracking German ciphers working in the famous Admiralty Room 40. He arranged for Wright to travel up to Liverpool Street Station on the footplate of a specially chartered locomotive. Hall realised the intelligence bonanza in his hands and put Wright to work building a chain of wireless intercept stations for the Admiralty. British radio operators were organised as the basis of the Royal Navy radio intercept service, feeding traffic to Admiralty Room 40 for cryptanalysis.

The intercept stations set up in this effort were known as the ‘Y’ stations. Marconi receiving stations, British Post Office stations and even an Admiralty ‘police’ station all provided intercepts to Hall's Room 40 code breakers. These stations were soon joined by enthusiastic amateurs including Barrister Russell Clarke and Col. Richard Hippisley had been logging intercepts of German traffic at their amateur stations in London and Wales. New intercept stations soon went up on the coast and within weeks practically all German naval wireless traffic found its way to Room 40.

The German high power long wave station at Norddeich provided huge volumes of fodder for the code breakers through the Y stations, which also soon turned to higher frequency interception as well. In 1915 these intercepts helped the British to win the naval battle at Dogger Bank and played vital roles in later naval engagements.

In the end the system was so successful that every single wireless message transmitted by the Germans throughout the war, in all, some eighty million words, were intercepted by Marconi operators and passed on to the appropriate Government authorities.

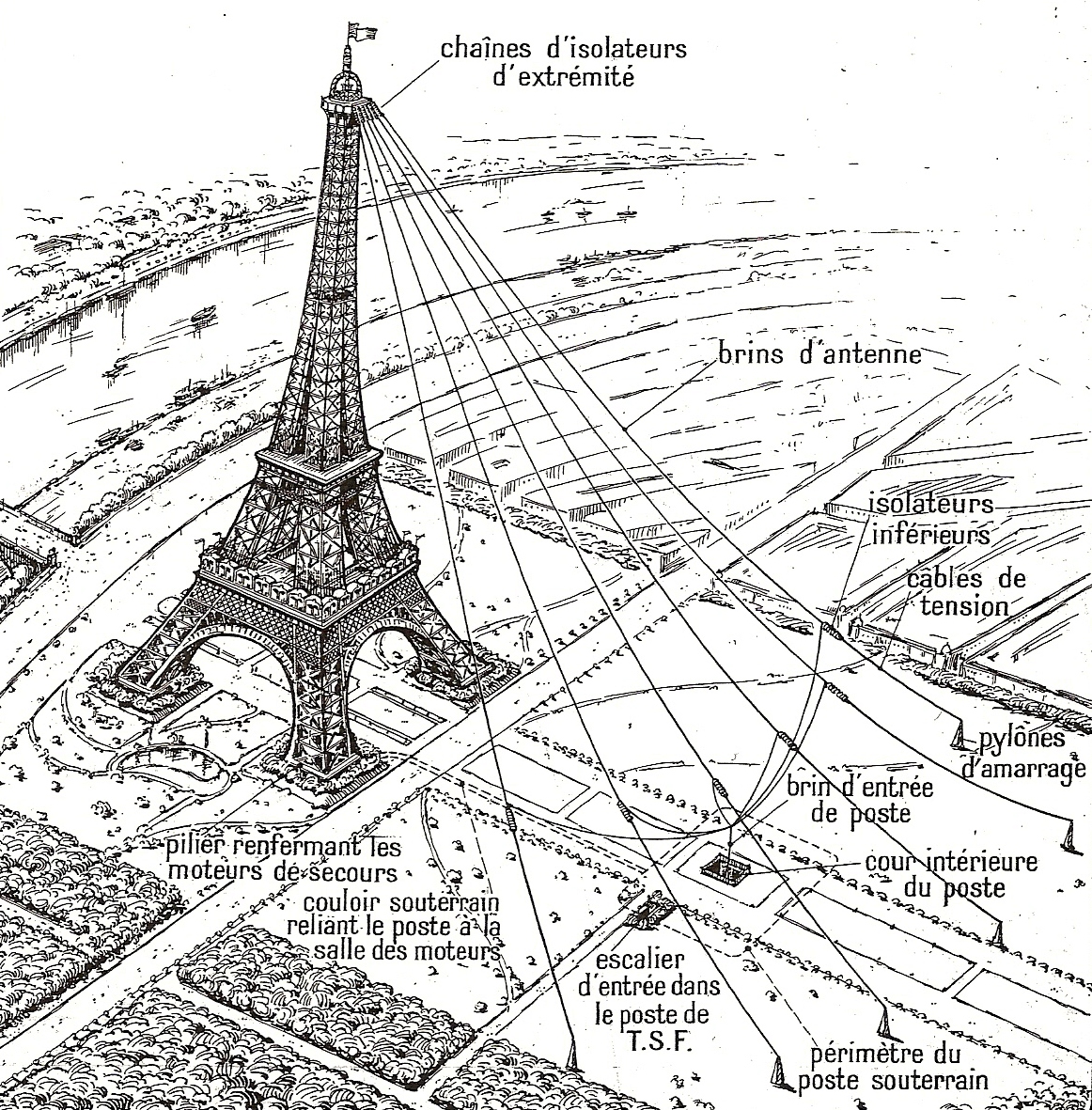

One key player in the German intercept 'business' was the French Military who through Commandant Cartier developed a sophisticated system that used very tall aerial masts, including the Eiffel Tower, allowing even relatively small transmitters in Germany to be picked up and their position triangulated and plotted. Even without breaking codes this could provide the Allies with valuable information. France created a special unit, the 8e Régiment de Transmissions, for just this work. Working under Cartier its HQ was located beneath the Eiffel Tower.

Guard at the Eiffel Tower wireless Station, c. 1915

Eiffel Tower antenna, 1914

This first wireless station was installed in 1908, then destroyed by flooding in 1911 and then rebuilt again. Six antenna strands down to the ground of the Champ-de-Mars with tension cables connected to docking pylons before entering a square well in the underground wireless station.

The collection and analysis of such data would today be called ELINT (ELectronic INTelligence). As early as the beginning of 1915 Cartier could give the French High-Command a complete organisation chart of the German armies. For some inexplicable reason the German army in the West made the very errors from which they had profited from in the East. At the beginning of the war the Germans sought to thrust into France to defeat the French armies east of Paris. The French had the whole order of battle mapped out by radio intercepts and up to the minute tactical intelligence. Just as the Russian thrust failed in the East for want of radio discipline, so to the German thrust in the West turned to defeat at the Battle of the Marne for exactly the same reasons.

It was also found that every wireless operator tapping out Morse signals had their own style or ‘fist’ by which he could be ‘identified’ even when transmitting coded messages. To try and avoid this the French even experimented with a Morse key that used an oil filled relay to smooth out the operator’s own rhythm. If an operator who had been previously identified as being part of the HQ of a particular military unit was detected transmitting from a new location then this would suggest that the unit had also relocated. The volume of signal traffic and any changes in this could reveal a unit held in reserve being brought up to strength and preparing for battle.

Throughout the war tactical wireless intercepts by all belligerent signal services provide important battlefield intelligence, but radio deception also started to become a weapon.

In early September, 1914 the Russians intercepted a message from the German Army Staff Headquarters from which the Russians inferred a threat from a new large force, and therefore held back considerable forces of their own in the upcoming battle. The German Eighth Army staff, however, anticipating interception, had transmitted a completely false message in plain text from its station at Koenigsberg. Radio deception and misdirection thus began to play its counterpoint to radio interception and the Germans used radio deception again successfully within weeks.

Spies and Espionage

As early as November, 1914 there had been a call in the British press for the use of private wireless stations to monitor for spy transmissions out of England.

While there is no evidence of any wireless transmission associated with spies and espionage out of England during the war, the demand of the amateur radio fraternity to be useful was met and the system that would be so effective in the next war was both anticipated and developed.

During the war the French service did uncover the location of one German espionage network in the French port of Marseilles, on the French Mediterranean coast. The German agents were sending to German Navy Command in Berlin information about the allied ships' and convoys' routes and times of the ships' and the convoy's departures from Marseilles. After that, German Navy Command sent the information and orders, by high-powered German radio station 'Nauen', to German U-boats operating in the Mediterranean. Co-operation between the agents in Marseilles, the German Navy Command in Berlin and the German submarines in the Mediterranean was excellent. Finally, the German agents were uncovered and captured. The British and French worked together on monitoring of German diplomatic messages from Madrid (Spain) to Berlin and vice versa.

In 1918 British intelligence sent Sir Hercules Langrishe and A.E.W. Mason to destroy the German wireless station in Mexico at Ixtapalpa in 1918. This Mason did by smashing its Audion valves, putting the German agent Herr Jahnke out of business.

The direction finding stations working under Captain Round also provided intercepts to Room 40. The directional aerials tracked U-boats and Zeppelins as well as naval craft.

The Y station intercepts also showed that the 1915 sinking of the Lusitania had the approval of the German high command, despite its continual denials. This along with the infamous intercepted 1917 ‘Zimmerman’ Telegram, in which Germany promised Mexico it could have back the territory it lost in the Mexican American War, if it would join Germany against the United States was later instrumental in bringing America into the war.

The leading history of the astonishing success of British intelligence in the First World War concludes that: ‘[the] Y stations made it all possible.’

Paradoxically the success of British Army signals units in intercepting German wireless traffic in turn partly convinced British commanders that wireless was too dangerous to use and at times the signals units were turned almost exclusively to monitoring and intercept work.

During the First World War Radio intercept operators were largely unsung heroes; their war was not one of combat so much as one of discipline. Much of that work had to remain top secret.

Wireless interceptors have tuned their radio receivers all over the world for nearly a hundred years, often subject to all the risks of war, often in appalling conditions, often for impossibly long shifts, often without relief for weeks, striving for perfect copy of enemy traffic. After the First War wireless signals were rarely sent in plain language so the intercept operators could almost never understand the traffic they took down. They knew only that the signals came from an enemy and that they put their countrymen in deadly peril, and they did their duty. The silent radiomen who listened in on both sides of many conflicts have earned the respect due to worthy adversaries.